Humility and Height: A Rookie Ascent to the Summit of Cotopaxi

Saturday, June 23rd

10:30 a.m.

My guide for the weekend, Diego, picked me up from the corner of Granados and Isla Marchena, the streets where I live here in Quito, Ecuador. My host mom is waiting with me to make sure that Diego is a real guide and I’m not about to hop in the car with someone who wants to sell me.

As we spoke, mostly in Spanish, it turns out Diego is a great guy. He’s 48, has a wife, a son, and a daughter, and in the 25 years he’s been a guide, he’s climbed just about every mountain and volcano in Ecuador. He’s even visited the US to climb Denali but had to call it quits before the summit due to altitude sickness, proving that the height can get to anyone, even with the best training. Not too reassuring for me, who at this point had climbed just one volcano, Rucu Pichincha, twice, at just over 15,000 feet. Other than that, the majority of my life had been contained to the rolling dirt mounds of north Louisiana, stretching at its highest point to a soaring 535 ft. at the summit of Driskill Mountain in Bienville Parish.

As Diego and I drove out of Quito, I couldn’t help myself but to ask the name of every peak I saw breaching the skyline and, of course, if he’d climbed it, to which he replied ‘yes’ to each and every one.

“How many times have you climbed Cotopaxi?”, I asked.

The look on his face told me he was trying to reach a number he couldn’t come up with.

“Hmmm…ahh…pienso (I think) …hmm”, which I gathered meant too many times to count. Although I was about to attempt to summit the second-highest volcano in Ecuador, higher than any mountain in the U.S. save Denali in Alaska, from his words I was made slightly less nervous, and was left with a sufficient amount of relatively unfounded confidence. Soon, the crammed and cornered streets of Quito faded into the rearview as the outskirts of the capitol city morphed into wider, more open spaces on each side of the highway, occupied only by the occasional vendor or fruit stand.

12:00 p.m.

Diego and I turned onto the tree-lined dirt road leading to the PapaGayo Hostería, just outside the small highway town of Machachi. We pulled into the hostel to be greeted by a woman standing on the front steps, who turned out to be the receptionist, manager of both room and gear rental, gear fitting assistant, and waitress. In fact, I didn’t see anyone else working at the hostel other than the squat Ecuadorian man working in the garden behind the building. Our hostess led us to a small shed in the back-left corner of the property, which had a spacious backyard and a suspended wooden bridge for the three resident goats, who chewed noisily as we passed.

The gear shed contained 20 or 30 pairs of climbing boots, helmets, ice axes, harnesses, crampons, and layers and layers of fleece and polar wear. I communicated that I had no idea my European size in footwear and ultimately had to compare my foot to Diego’s and guess from there. The boots were noticeably uncomfortable, and I immediately felt a notch in the heels perfect for grinding out blisters. Nevertheless, I was glad to be there, so I said nothing but “gracias, perfecto,” as I paid the $20 rental fee and walked back past the goats to a hot meal. As is the unbreakable standard in Ecuador, lunch was a hot soup, a large entrée, and always, always, a dessert.

As Diego and I sorted through the gear I had brought with me, he and I both realized that I didn’t need and, as a matter of fact, couldn’t afford to carry the extra weight of most of it. Of my things, he picked out a pair of gloves I’d borrowed from my host brother, my Camelbak, also borrowed, a windbreaker, and my Georgetown hoodie. The rest I stuffed in a bag and left with the kind lady at the hostel.

“Could I just leave it in the car?”, I asked.

“Ahh, no. En el parqueador, hay personas…”, and he made a breaking motion with his hand and pointed towards the window, “very bad.” he finished. I got the message.

1:30 p.m.

Diego and I slowed down to enter the lot of a small visitor’s center inside Cotopaxi National Park and stopped to pack all our things into the large adventure backpacks, leaving my soft, comfortable hiking boots hidden in the car in place of stiff, heavy, bright yellow climbing boots. We continued driving through the flattest fields I’d yet seen in Ecuador, home to gentle, winding rivers, large, thick boulders jutting out of the earth, and herds of wild horses grazing in the knee-high grass under the shadow of the volcano.

Arriving in the parking lot around 2 p.m., the dust settled around Diego’s old Toyota Prado as we hoisted our bags out of the backseat to begin the hike up to the José Rivas Refuge, basecamp for most of those hoping to ascend Cotopaxi. At this point in the day, the volcano itself was hidden high in the clouds, out of sight.

As I learned near the summit of Rucu Pichincha, sand is not ideal hiking terrain. At a 35° angle with three extra pounds on each foot and another 50 on my back, the ‘short’ hike up to the refuge, which is in sight for the duration of the hike, turned out to be a humbling introduction for what was to come. As I took the hike step by step, Diego quickly grew farther and farther ahead in a methodical march he’d likely done a hundred times.

2:30 p.m.

Drawing ragged breaths, I stumbled onto the stone porch of the refuge to meet Diego, who’d effortlessly arrived ten minutes earlier. I ducked under the doorway to avoid knocking the hilt of my ice axe against the wooden frame and entered the quaint mountain refuge. I quickly learned that the air in the building, nestled into the side of the volcano, just under a two-hour hike from the lowest edge of the glacier, was unheated and just as frigid inside as outside.

The interior walls were filled with flags from around the world, as well as the people who had carried, tacked, and signed them. Although I heard mostly Spanish of many different dialects, I caught clips of conversation in Chinese and English as well. Diego spoke with the manager, clearly an old friend, who placed two small keys in his hand. I followed the two of them up the short staircase, lined with Crocs for wear around the refuge, to a room occupied by roughly 20 bunk beds, lined wall to wall. Diego showed me to my top bunk and handed me the key to the small drawer underneath, #43.

“$10 si lo pierdes,” said the manager. $10 if I lost the key. I zipped it into the breast pocket of my windbreaker.

“Meet me downstairs in 15 minutes for una bebida caliente,” Diego told me. A hot drink sounded welcoming in the cold cabin air, so I quickly unpacked my things and headed downstairs.

3:30 p.m.

I couldn’t find any Crocs that fit me, so I was limited to stomping around the refuge in my climbing boots. After I’d unpacked my gear and unrolled my sleeping bag, I very loudly made my way downstairs where I came across a heater and a young woman curled up next to it. I sat on the floor cushion to warm up and we started talking. Although I began in Spanish, she could obviously tell from my accent that I was not a native speaker and successfully assumed that I spoke English as well.

Switching back and forth between the two languages, I learned that her name was Natalia, and she was waiting for her friends to come down the mountain. Somehow her feet had gotten wet climbing up to the refuge, so she was warming her boots by the fire. She worked for an advertising agency in Miami, but she was originally from Bogotá, Colombia. She was enjoying the U.S., but was disappointed to find that, while she had moved to learn English, everyone in Miami spoke Spanish, and it was often confusing having to know when to switch between the two.

I told her that I was from Louisiana, which is relatively close to Florida. I told her that I’d spent a little more than a month in Ecuador already (she cut in to tell me that the weather in Colombia was much nicer), and that this was my first serious mountain climb. I mentioned that my Dad had been a climber, but it became more difficult after he fell from a frozen waterfall and broke his legs, and even more so after moving to Louisiana, where there are no mountains. Almost an hour later, I decided to find Diego for that hot drink and wished her luck finding her friends.

5:30 p.m.

By this point, still wearing all my clothes, I’d settled deep into my sleeping bag upstairs and fallen asleep listening to the first chapter of Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. Diego woke me at 5:30 to tell me that dinner was ready, so I once again squeezed into my climbing boots and clambered downstairs to sit with Diego and the other guides.

They of course conversed in Spanish, which I mostly understood but chose to listen instead. When Diego finished his dinner with food left on his plate, the guide next to me joked,

[translated] “Diego, you have to finish, the kids in Africa don’t even have food!”

I’ll admit, I laughed, but the men around me grew silent.

Looking straight to Diego, the man asked: “He knows Spanish?”

Diego nodded, looking at me, relieved, as if he was proud to have a rare bilingual client after 25 years of working to communicate in his non-native language. The other guides did not speak as much after that.

After dinner, Diego walked me over to a map posted on the wall to explain the route, the terrain, the gear, the footwork, and anything else I needed to know about the climb ahead. At this altitude, it was very important that I knew everything before I found myself in a situation where I needed to know it and didn’t.

“I’m going to ask you every hour or so how you feel,” he spoke in English to make sure I understood. “Do you see la Roca Negra? (See map below) This is where I will start asking you every 10 minutes.” Cotopaxi was a very serious undertaking, he told me, and I needed to be physically and mentally prepared.

Shortly after, I shuffled up the stairs and zipped into my sleeping bag.

11:00 p.m.

I was awoken by the flicker of lights and the sounds of climbers getting geared up for the ascent around 11 p.m. Diego told me I could get up at midnight since I’d likely acclimatized a little better and didn’t need to start as early as the others. Even so, the combination of the fluorescent lights and the sounds of 30 other climbers zipping, buckling, and securing their things kept me awake, so I laid under the light listening as Harry Potter accidentally inflated Aunt Marge at the Dursley’s on 4 Privet Drive.

At midnight I threw on my many layers and blanketed my heels in Band-Aids to soften the inside of my climbing boots. Downstairs, I set my pack down by the long dining table and smeared butter across a cold croissant, filling my thermos with what I thought was tea before a fellow climber tapped my shoulder and asked if I was intentionally emptying hot water into my HydroFlask. I thanked him and filled the remaining space in my thermos with fresh yerba mate.

By 1 o’clock Sunday morning, we were ready to begin the ascent.

1:00 a.m., Sunday, June 24th

Diego and I began climbing up the loose dirt and rock at 16,400 feet, already higher than I’d ever been before, a fact I was quickly reminded of by the reduced amount of oxygen in the air. My borrowed CamelBak froze almost immediately, rendering it useless. An hour into the hike, I noticed that the Band-Aids, although to some extent had softened the pain in my heels, served only to delay the blistering. By the start of the second hour as we approached la entrada al glaciar, I could already feel the warmth of tearing skin and blood under my socks. However, it quickly coagulated and froze.

2:20 a.m.

Diego dug the hilt of his ice axe into the frozen terrain, which by this time I had learned meant it was time to rest. This was a welcome signal. He told me to start unpacking the heavier polar gear, such as my outside gloves and crampons. With a point of my headlamp I could see the ground beginning to turn from a rich brown to a dusty white. To my right stood large, jagged walls of ice, their outlines illuminated by the light of the full moon.

Crampons, to begin, are a truly magical invention, though I didn’t fully realize this until much later. Whether it was the brief rest, the few sips of Gatorade, or the prospect of a change in terrain, I suddenly felt a wave of energy as I quickly found I was able to walk over and grip just about anything with my new feet. In my best impression of Jon Snow, I knew absolutely nothing.

3:30 a.m.

My energy boost diminished at an astonishing rate. Not ten minutes after I’d affixed my crampons to my climbing boots, I was back to huffing and puffing every 15 yards up the snowy switchbacks. Diego and I had tied together before stepping onto the glacier, and the tug of the purple climbing rope looped in a figure-eight to the front of my harness had become all too familiar as he continued at a steady pace up the side of the volcano. Behind him I followed like a dog on a leash, exerting much more effort than the seasoned mountaineer pulling me along.

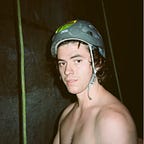

With a welcomed plunging of Diego’s axe into the snow we arrived at what appeared to be a common resting place for weary climbers. A snowstorm had begun, and a thin layer of crunchy ice had spread across everything exposed to the elements. The short tuft of my dark brown hair sprouting from under my helmet had become 7 or 8 icy white tendrils, blowing energetically in the howling wind in front of my eyes.

“How much left?”, I asked.

“Depending on the weather, three, maybe four hours,” answered Diego nonchalantly.

I took a few more sips of slushy mandarin Gatorade, and we pressed on.

5:00 a.m.

We are above the clouds. I believe that we’ve passed Roca Negra at this point, but there’d been no real way to be sure under the dark sky. Although the sun had now just about risen, nothing is visible below the clouds, and above them only a short stretch of snow can be seen leading up to where we’ve come to briefly rest.

To be blunt, the altitude is now officially kicking my ass. Above 18,000 feet, every step is challenging. I’ve taken entirely to ramming one pointed foot into the snow and turning the other perpendicularly to push upwards in a sort of torturous crabwalk up the slope, using the hilt of my ice axe for support, blade always pointed inward in case I fell and needed to self-arrest. I would switch my angle each time the pain in my calves and thighs would grow too great to continue. My breaths were quick and short as my lungs did their very best to extract as much oxygen from the air as possible.

Every now and then I would look up and see a bluff and think, oh, that must be it, we’ve gotta be close, only to be disheartened at the sight of another face peeking over its edge. As we climbed higher and higher, it seemed as if the volcano grew higher as well. But by 5:30 a.m., the summit was finally, finally in sight. I wanted to take a picture, but to remove my gloves at temperatures well below 0° F would have been reckless.

6:00 a.m.

Each fervent point of the toe and labored push upward is agonizing. My breaths are rapid and shallow. My legs and lungs are screaming. My vision is blurry, my head is pounding, my stomach feels as if it’s being kneaded by the intrusive hands of an angry baker. Diego asks if I’m alright, but with the summit in sight, I lie and say, “yes” in between labored breathing and a hacking cough.

[Translated] “There are just two more slopes,” he says, “and then we’re there. Do you want to turn around? It’s very dangerous if you’re exhausted for the descent. That is when 80 percent of accidents happen.”

“¿Cuánto más?” I croaked. How much more.

“Cuarenta minutos,” he replied. 40 minutes. “We can turn back.”

“No,” I gasp, “let’s go.”

I look up to see the longest, steepest slope yet and immediately feel defeated. As we approached, I was unsure whether or not I would be able to carry myself to the switchback. I was afraid I’d buckle and begin sliding downward. I took five more steps up the slope before collapsing again, breathing more rapidly than I had the entire ascent. As I saw the purple rope grow tighter and felt the familiar tug on my harness, I dug my axe into the snowbank to my right and elected to crawl, bit by frozen bit. 12 minutes had now passed since I had begun the short ascent up the slope; I had achieved maybe 20 yards. But despite the storm raging around me and my helmet slipping forward constantly with the weight of my frozen headlamp, the outline of the summit was still in sight. I pushed forward.

6:20 a.m.

One slope left. I can see people standing on the summit, huddled in a pack to preserve warmth, steadying themselves on one another against the gale force wind. By now I have resorted totally to crawling at a speedy pace of about two yards a minute. My hands, feet, nose, and ears have gone completely numb. Water had somehow been trapped under my fingernails, where it had frozen, and the rapid expansion had ripped the nails from their beds. The inside of my boots is a frozen mess of rocks, sand, blood, and snow. My facemask is a frigid sheet of sweat, snot, and saliva. I’m breathing through my mouth as the insides of my nostrils have crystallized. But I’m just 20 yards out.

One would, at this point, think to be greeted by a feeling of impending achievement to lift the spirits and grant a second wind. But, seeing as there was plenty enough wind around me and very little oxygen in my brain to provide the mental strength to truly reconcile where I was, the final 10 minutes of the climb were no less excruciating than the previous 10. Suddenly, to my great relief, the ground flattened out, and I looked forward.

Diego had stopped walking, and instead had his arm outstretched, pointing towards the small, rough circle of snow making up the summit area. He ushered me forward, graciously ensuring that I would reach the summit first. I jammed my axe into the ice, got on one knee, then the next, and pushed myself up, willing myself through the last 10 steps to the summit of the volcano.

6:44 a.m.

I reach the center of the circle, take a brief look around at the steel gray sky surrounding the summit, and collapse. With snow and hail swirling around me, I crawl to a snowy bank strong enough to prevent me from rolling backwards off the volcano, and there I sat as a weak smile spread across my face. 45 minutes prior I had been ready to quit. I thought of Humboldt, the geographer who’d dreamed of sitting where I was sitting. I thought of my parents, my brother and my girlfriend, probably worried sick at this point having not heard from me for 15 hours. I thought of Diego, the man who’d just dragged me 6 hours up the side of the mountain and risked his fingers to take a picture of me with his phone — despite layers of clothing and a LifeProof case, mine had gathered a thick layer of frost and ceased to function. But sitting in the hard snow, three and half miles into the sky, with the whole of Ecuador spread out before me under the clouds, I thought mostly about how grateful I was just to be there.

6:49 a.m.

“Okay, vamos,” shouted Diego through the wind. It was clear that the weather was growing dangerous, if it had not been already. Even the circular expanse of Cotopaxi’s crater was hidden under a thick layer of snowy fog, and I was less than eager to approach the edge with the wind blowing as strong as it was.

“You lead,” he said. I didn’t stop to think about what that meant. At this point I was just taking commands. I stood and grabbed my ice axe, taking the first step down the mountain when my crampons caught one-another, and I immediately fell back down into the snow.

“Cuidado,” he said from behind with a warm laugh. I got back on my feet and continued down. The descent was not nearly as difficult as the climb up. Still, I knew to be careful.

Having reached the summit, I had finally found that second wind I had so long been after. What more, I was finally able to see exactly what it was that I’d climbed. Miles of steep, snowy trails switched back and forth in front of me. I had crossed natural ice bridges over vast crevasses, too deep to see the bottom. I had climbed far above the clouds. I had passed over potholes in the path opening up to frozen, endless depths without so much as a glance. I had crawled hand and knee (and axe) up the last 200 yards to the summit. In complete honesty, the early morning darkness and obscurity of the storm had done me a favor. In clear weather, with the entirety of the steep ascent before me, I’m not sure I would have been able to stomach the sight of it.

8:42 a.m.

The trails had flattened somewhat into a thin path along the side of the mountain. Headed forward into a gusting wind, I lead the way along a particularly precarious ridge that passed between a large wall of ice and snow on the right, and a cavernous, yawning crevasse to my left.

As I carefully chose each step, the wind suddenly doubled in strength and I was nearly thrown backwards into Diego. My left crampon caught the ice, and I immediately went down to one knee. Frantically gripping the hilt under the blade of my axe and securing it under my right arm, I dug the point into the snowbank as the wind did its utmost to blow me over the edge and into the abyss. After 2 minutes of continuous effort and constant re-securing, the wind finally backed off.

“Okay,” said Diego. “Continue.”

And so we did.

9:00 a.m.

Diego and I had just stopped when he shouted, clearly excited by something behind me.

“Look!” he said. “Photo, go stand there, now!”

I turned to look and suddenly found myself staring in awe at the sight. The clouds over the summit had finally cleared, and for the first time I was able to fully absorb the majesty of Cotopaxi. It burst into the sky with indescribable natural force, towering over every mountain in sight by thousands of feet.

So, as I had been doing for the past eight hours, I humbly did what I was told. I stood, and Diego took a photo.

9:46 a.m.

Having taken off my crampons and polar gloves at the lower edge of the glacier, I arrived at the José Rivas Refuge just before 10 a.m. on Sunday morning. I had spent the last half hour learning to walk again through the loose dirt and gravel without the assistance of crampons, and, after the fifth or sixth fall, I elected to stumble and butt-slide the remainder of the way down. I staggered into the refuge to be greeted by the smiling face of congratulations from the refuge manager and the weary but supportive looks of other climbers. I was served a hot Ecuadorian breakfast of fresh fruit and a corn tamale, accompanied by the best hot chocolate I have ever had. Shortly after, I packed up my things, made the descent to the parking lot and headed home. By 3 p.m., I was back in Quito and found myself fed, showered, and fast asleep, succumbing to the sheer exhaustion.

Those who travel to mountain-tops are half in love with themselves, it is said, and half in love with oblivion.[1] There is nothing at those mountain tops but that which cannot be effectively expressed, free from subjection to the bleak confinement of words. Yet, ultimately, it is the intangible which we seek nonetheless.

Robert Kyte

June 25th, 2018, Quito, Ecuador

[1] Macfarlane, Robert. Mountains of the Mind: A History of a Fascination. Granta, 2017.